From recent research, it is clear that to avoid the worst climate impacts, global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will not only have to be cut in half by 2030, then reach net zero by mid-century.

Recognizing this urgency, an unprecedented number of business leaders and local governments are supporting strong national climate ambition through the Race to Zero campaign of the UN’s high-level climate champions. The global initiative establishes minimum criteria to design net zero targets, asking regions, cities, companies, investors and civil society to commit to reaching net zero emissions by 2050 and present a plan before the next UN Climate Summit. in 2021. This comes on the heels of the UN Secretary-General asking countries to present net zero targets. In addition, an increasing number of countries have joined the Climate Ambition Alliance with aspirations to achieve net zero emissions.

Here we explore what a net-zero target really means, try to understand the science behind net-zero, and discuss which countries have already made such commitments.

1. What Does It Mean to attain Net-Zero Emissions?

We will achieve net zero emissions when the remaining human-caused GHG emissions are offset by removing GHGs from the atmosphere in a process known as carbon removal.

First, human-made emissions, such as those from vehicles and fossil fuel factories, need to be reduced as close to zero as possible. Any remaining GHGs would be balanced by an equivalent amount of carbon removal, for example by restoring forests or through direct air capture and storage (DACS) technology. The concept of net zero emissions is similar to “climate neutrality”.

2. By when does the World Need to Reach Net-Zero Emissions?

Under the Paris Agreement, countries agreed to limit warming well below 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) and ideally 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F). Climate impacts already unfolding around the world, even with just 1.1 degrees C (2 degrees F) of warming, from melting ice to devastating heat waves and more intense storms, show the urgency to minimize the temperature rise to no more than 1.5 degrees C.

The World research institute’s report on Global Warming of 1.5 ° C, of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), concludes that if the world reaches net zero emissions a decade earlier, by 2040, the possibility of limiting warming to 1.5 ° C is considerably higher. The earlier they reach peak emissions, and the lower they are at that point, the more realistic it is that we will achieve net zero on time. We would also need to rely less on carbon removal in the second half of the century.

Importantly, the time frame for reaching net zero emissions differs significantly if one refers to CO2 only or if one refers to all major GHGs (including methane, nitrous oxide, and “F gases” such as hydrofluorocarbons, commonly known as HFCs). For non-CO2 emissions, the net zero date is later because some of these emissions, such as methane from agricultural sources, are somewhat more difficult to remove. However, these powerful but short-lived gases will drive higher temperatures in the short term, potentially pushing the temperature change beyond the 1.5 degree C threshold much earlier.

Because of this, it is important for countries to specify whether their net zero targets cover only CO2 or all major GHGs. A comprehensive net zero emissions target would include all major GHGs, ensuring that non-CO2 gases are also reduced.

3. Do we All Need to Reach Net-Zero at the Same Time?

The timelines above are global averages. Because the economies and stages of development of countries vary widely, there is no single timeline for all countries. However, there are strict physical limits to the total emissions that the atmosphere can support while limiting global temperature rise to the agreed targets of the Paris Agreement.

At the very least, major emitters (such as the United States, the European Union, and China) should achieve net zero GHG emissions by 2050, or it will be difficult for the math to work regardless of what other countries do. Ideally, the major emitters will reach net zero much earlier, as the largest economies play a huge role in determining the trajectory of global emissions.

4. How Many Countries Have Net-Zero Targets?

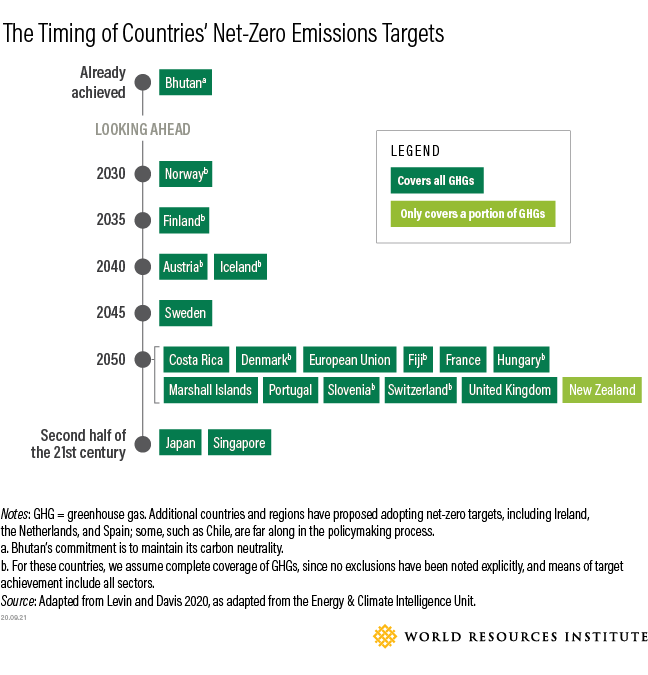

Twenty countries and regions adopted net zero targets as of June 2020: Austria, Bhutan, Costa Rica, Denmark, the European Union, Fiji, Finland, France, Hungary, Iceland, Japan, the Marshall Islands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

This list only includes countries that adopted a net zero target in law or other policy document. This does not include targets in political speeches, such as China’s notable announcement. The Climate Energy and Intelligence Unit maintains an up-to-date list of zero net ads here. As of June 2020, 120 countries have committed to working on net zero targets through the Climate Ambition Alliance, including all least developed countries and a handful of high-emitting countries. However, only about 10% of global emissions are covered by some kind of adopted net zero target. Some net zero targets have been incorporated directly into countries’ commitments under the Paris Agreement.

5. How to Achieve Net-Zero Emissions?

Policies, technology and behavior must change across the board. For example, on 1.5 degrees C trips, renewables are projected to supply between 70% and 85% of electricity by 2050. Energy efficiency and fuel switch measures are essential for transport. Improving the efficiency of food production, changing dietary options, halting deforestation, restoring degraded lands, and reducing food loss and waste also have significant potential to reduce emissions. It is critical that the structural and economic transition needed to limit warming to 1.5 degrees C is addressed fairly, especially for workers in high-carbon industries. The good news is that most of the technologies we need are readily available and increasingly cost-competitive with high-carbon alternatives. Solar and wind power now provide the cheapest energy for 67% of the world. Markets are realizing these opportunities and the risks of a high-carbon economy, and are changing accordingly.

In addition, investments in carbon removal will be necessary. The different pathways assessed by the IPCC to reach 1.5 degrees C depend on different levels of carbon removal, but they all depend on it to some degree. It will be necessary to remove CO2 from the atmosphere to offset emissions from sectors where reaching zero emissions is more difficult, such as aviation. Carbon removal can be achieved by various means, including terrestrial approaches (such as restoring forests and increasing carbon sequestration from the soil) and technological approaches (such as direct air capture and storage or mineralization).

6. Does the Paris Agreement make Countries Commited to Achieve Net-Zero Emissions?

In short, yes.

The Paris Agreement has a long-term goal of achieving “a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century, on the basis of equity and in the context of sustainable development and efforts to Eradicate poverty. ” The concept of balancing emissions and removals is similar to achieving net zero emissions.

Along with the ultimate goal of limiting warming to well below 2 degrees C, and aiming at 1.5 degrees C, the Paris Agreement commits governments to drastically reduce emissions and increase efforts to achieve net zero emissions. in time to avoid the worst consequences of climate change.

Commitments to creating bold short- and long-term goals that align with a future of net zero emissions would send important signals to all levels of government, the private sector, and the public that leaders are betting on a safe and prosperous future. rather than one devastated by climate impacts.